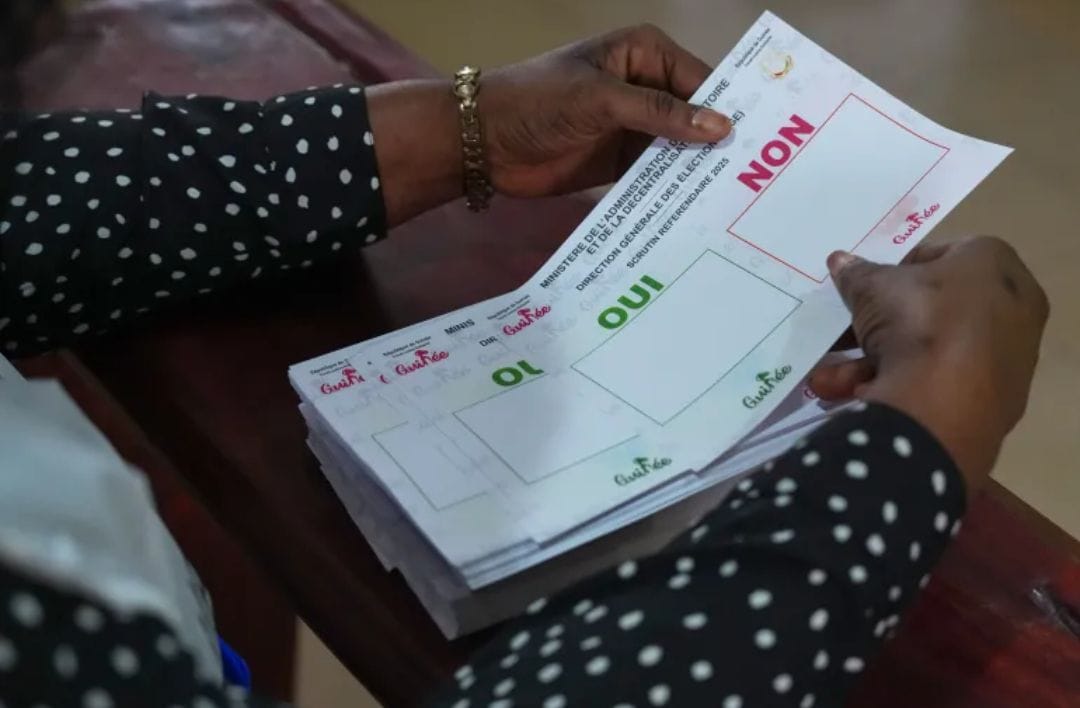

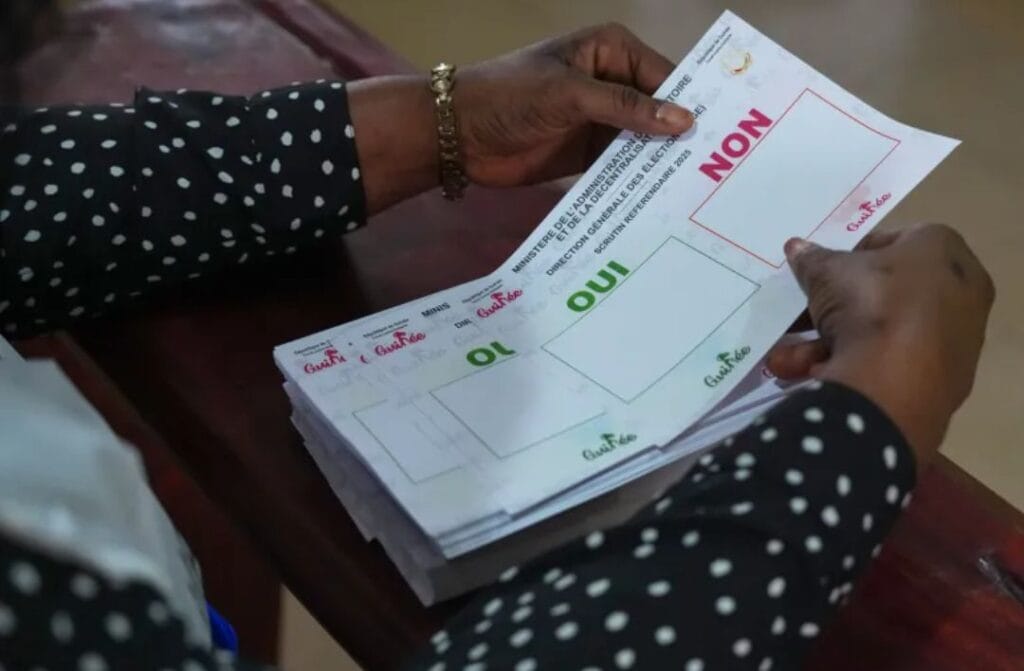

The Guinea constitutional referendum opened on Sunday, drawing the country’s 6.7 million eligible voters to polling stations in a historic decision that could transition the nation from military to civilian rule.

The Guinea constitutional referendum seeks to approve a new constitution that would extend the presidential term from five to seven years, create a Senate with one-third of members appointed by the president, and potentially allow coup leader Mamady Doumbouya to stand in upcoming elections.

In Conakry, voters queued early at polling stations, eager to cast their ballots in what many are calling a pivotal Guinea constitutional referendum.

“People are expecting that the referendum will result in the approval of the draft constitution, which some see as impressive and progressive,” said Ahmed Idris, reporting from the capital.

He added, “However, opponents fear it will legitimise military rule and allow members of the current government to participate in elections, despite a transitional charter barring such involvement.”

Security has been tight during the Guinea constitutional referendum, with authorities deploying more than 40,000 personnel to ensure the vote remains orderly. Campaigning was banned in the two days prior, a move critics say limits political discourse.

Nonetheless, citizens showed determination to exercise their right to vote. “We are here because this referendum is our chance to shape the future of Guinea,” said Mariam Keita, a local teacher.

Critics of the Guinea constitutional referendum argue that it represents a consolidation of power by the military government.

Since seizing power four years ago, Doumbouya’s administration missed a December deadline to return governance to civilian hands.

Observers across West and Central Africa have noted that eight coups since 2023 have reshaped the political landscape, making this Guinea constitutional referendum a potential precedent for the region.

Prominent opposition leaders, including Cellou Dalein Diallo and deposed former President Alpha Conde, have called for a boycott of the Guinea constitutional referendum, citing suspensions of their parties and alleged human rights abuses.

“The referendum is a façade to legitimize a military government that has consistently silenced dissent,” a representative from Diallo’s party said. Human Rights Watch has reported disappearances of political opponents, though the government has denied these claims.

Despite opposition criticism, many citizens expressed support for the Guinea constitutional referendum as a pathway toward stability. “We need a clear framework to transition from military oversight to civilian governance,” said Ibrahima Sow, a civil servant in Conakry. “This referendum is our opportunity to set the rules for future leadership and ensure our voices are heard.”

The Guinea constitutional referendum also raises questions about regional democracy. Analysts suggest that if passed, the new constitution could reinforce the power of the sitting government while shaping the country’s legislative structure for years to come.

The creation of a Senate, where one-third of members are presidential appointees, has been particularly controversial, as critics argue it could undermine checks and balances.

Voter sentiment during the Guinea constitutional referendum has been mixed. Some citizens see it as a chance for progress, while others remain wary of potential manipulation.

“We are skeptical, but we must participate to make sure our concerns are reflected,” said Fatoumata Diallo, a small business owner in Conakry. The referendum is widely regarded as a litmus test for Guinea’s commitment to democratic norms after years of military control.

International observers are monitoring the Guinea constitutional referendum closely. African Union representatives have highlighted the importance of transparency and fairness, urging the government to ensure that the process is credible.

“The eyes of the continent are on Guinea. The outcome of this referendum will influence perceptions of democratic transition across West Africa,” one official said.

The Guinea constitutional referendum coincides with rising political awareness among citizens, many of whom have grown frustrated with military-led governance. “We want a system where our votes actually count, where we can elect leaders who are accountable,” said Alpha Camara, a student in Conakry.

The new constitution, if approved, could pave the way for broader reforms, including institutional strengthening and civil liberties protections.

While the military leader has not confirmed whether he will run in the presidential election scheduled for December, the Guinea constitutional referendum has sparked debates over eligibility.

Critics warn that allowing coup leaders to participate would contravene the principles of the transitional charter. “This referendum could redefine the rules to fit the rulers rather than the people,” said a political analyst.

The Guinea constitutional referendum also reflects broader trends in West Africa, where military governments have been increasingly challenged by citizens’ demands for democratic accountability.

“Voters are no longer passive; they are actively shaping the political environment,” the analyst noted. The results of the referendum are expected within two to three days, and both supporters and opponents are bracing for potential unrest if the vote is disputed.

Public engagement has been high during the Guinea constitutional referendum. In Conakry and other urban centers, citizens lined up early, with families and community groups attending together.

“This is not just a vote; it is a statement about our future,” said Mariama Camara, a mother of three. The atmosphere was charged, with polling officials reporting orderly conduct despite the high turnout.

The Guinea constitutional referendum has prompted debates about fairness and legitimacy. Observers note that the process could set the tone for upcoming presidential elections and establish precedents for future governance. “This is a defining moment for Guinea,” said Idris. “It’s a referendum not only about a constitution but about the nation’s path from military rule to civilian leadership.”

As results are tallied, the Guinea constitutional referendum may either confirm the country’s commitment to democratic transition or intensify political tensions.

Citizens, opposition leaders, and international observers are watching closely, aware that the referendum’s outcome will have long-term implications for governance, civil liberties, and regional stability.

In conclusion, the Guinea constitutional referendum represents a critical juncture in the country’s political evolution. It embodies both hopes for democratic transition and fears of entrenched military power.

With over 6.7 million voters eligible to cast their ballots, the referendum is a decisive step that could shape Guinea’s governance for years to come, offering a blueprint for civilian oversight while testing the resilience of democratic institutions in a post-coup environment.