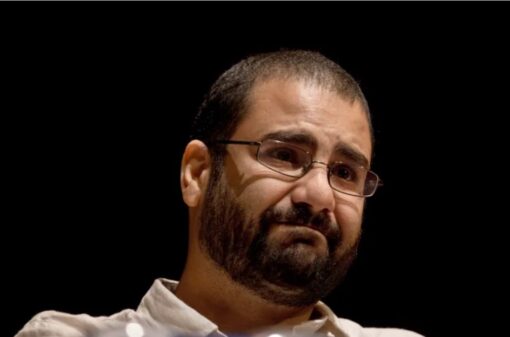

The announcement of an Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon by Egypt’s president has reverberated across Cairo, London, and international human rights circles, marking the end of one of the most high-profile imprisonment cases in recent Middle Eastern history.

The Egyptian-British activist, who became a symbol of the 2011 revolution and the global campaign for political freedoms, was officially granted a presidential pardon after years of mounting pressure from rights groups, Western governments, and his family.

The Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon is already being hailed as a breakthrough by international observers, even as others caution that Egypt’s wider human rights record remains deeply troubling.

Abd el-Fattah, now in his early forties, has spent much of the last decade behind bars. His repeated arrests and prosecutions were tied to accusations of spreading false news and undermining national security, charges that rights organizations insist were politically motivated.

Amnesty International once described him as “a prisoner of conscience whose only crime was daring to demand freedom.”

His supporters argue that the Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon is long overdue and the result of relentless international advocacy, particularly from the United Kingdom where his dual citizenship became a rallying point for campaigns.

The Egyptian presidency confirmed the pardon through a brief statement, noting that President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi had authorized the release as part of a wider initiative to reduce tensions and open space for national dialogue.

While officials framed it as a gesture of goodwill, analysts say the decision was also influenced by mounting diplomatic pressure. British leaders had repeatedly raised his case during bilateral meetings, and the United Nations had listed Abd el-Fattah among the emblematic prisoners of conscience in the Arab world.

“Today we breathe again,” his sister Mona Seif said in an emotional message on social media. “The Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon is a victory for persistence, solidarity, and love.”

The activist’s long ordeal became especially visible during last year’s UN climate summit, COP27, hosted by Egypt in Sharm el-Sheikh. Abd el-Fattah went on a prolonged hunger strike, drastically reducing his calorie intake to protest both his detention and the Egyptian government’s crackdown on dissent.

His hunger strike brought international attention, with several world leaders reportedly raising his case directly with Egyptian officials during the summit.

That moment highlighted the contradiction between Egypt’s role as host of a global conference and its domestic repression. The hunger strike was suspended after fears for his life grew, but the incident kept his name in headlines worldwide and may have laid the groundwork for the Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon that has now materialized.

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer welcomed the news, declaring that “the release of Alaa Abd el-Fattah is a moment of relief for his family and all those who campaigned tirelessly for his freedom.” He emphasized that while the Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon is a positive step, broader reforms in Egypt remain necessary.

“We must continue to urge Egypt to protect fundamental freedoms for all citizens, not just the high-profile cases,” he said. The UK Foreign Office likewise described the pardon as “a milestone in our continuing dialogue with Cairo on human rights.”

Reactions within Egypt were more restrained. Pro-government commentators praised President Sisi’s decision as evidence of his willingness to listen and compromise in the context of a national dialogue. Yet critics warned that the Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon should not overshadow the plight of thousands of other political prisoners who remain in detention.

“This is not about one man, no matter how prominent,” said Mohamed Lotfy, head of the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms. “We celebrate his release, but we remind the world that thousands more remain behind bars.”

For Abd el-Fattah’s family, the pardon ends years of torment. His mother, academic and mathematician Laila Soueif, said the family had endured cycles of hope and despair with each new arrest and trial. “We are grateful beyond words,” she said, “but we cannot forget the suffering of others who are still unjustly imprisoned.”

His family has long argued that his persecution was meant as a warning to Egypt’s youth that the dream of the 2011 revolution could not be revived.

The Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon, they believe, is a reminder that global solidarity can sometimes overcome even entrenched authoritarianism.

International human rights groups have greeted the development with cautious optimism.

Amnesty International said the Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon should be “the beginning, not the end, of a broader process to release all those detained for peacefully exercising their rights.”

Human Rights Watch called it a “testament to the power of international solidarity,” while stressing that Egypt must also improve conditions for detainees and roll back restrictive laws.

Analysts suggest that the pardon may serve multiple purposes for the Egyptian government: a goodwill gesture toward Western allies, an attempt to soften criticism ahead of important economic negotiations, and a strategy to rebrand Egypt as responsive to international appeals.

The Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon also has symbolic weight for the Arab world. Abd el-Fattah was among the first wave of bloggers and digital activists who used social media to challenge authoritarian rule during the Arab Spring uprisings. His writings and speeches inspired countless young people across the region.

That legacy made him both a hero to many and a persistent target for Egyptian authorities who viewed him as a destabilizing figure. His freedom now rekindles conversations about the unfinished business of democratic reform in Egypt and beyond.

From a geopolitical perspective, the timing of the pardon is significant. Egypt is facing acute economic challenges, with inflation and foreign debt rising sharply.

Securing international loans and investment has become a top priority for the government, and improving its human rights image could ease negotiations with Western financial institutions.

Observers note that President Sisi has occasionally used high-profile pardons in the past as bargaining chips in diplomacy. The Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon, therefore, may serve both humanitarian and strategic purposes.

What lies ahead for Abd el-Fattah remains uncertain. Friends say he is eager to reunite with his family and may eventually consider leaving Egypt for the UK, where he holds citizenship and where his case attracted widespread attention.

Yet others believe he may continue his activism in some form, given his lifelong commitment to political freedom. His release raises questions about whether he will be allowed to travel freely or whether new restrictions will be imposed on his movements.

For now, the world is watching closely. The Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon has been celebrated in headlines across Europe, the Middle East, and the United States, cementing his place as one of the most recognizable voices of dissent in the Arab world.

It marks a rare moment of convergence between international pressure and domestic decision-making in Egypt. Whether it signals a genuine shift in policy or merely a temporary concession remains to be seen.

As his supporters gathered outside his family’s home in Cairo to celebrate, chants of “freedom for all” filled the air. For many, the Alaa Abd el-Fattah pardon is both a personal victory and a collective reminder that the struggle for human rights in Egypt is far from over.